Mental Sickness: The Unexpected and Neglected Aftermath of the Covid-19 Pandemic.

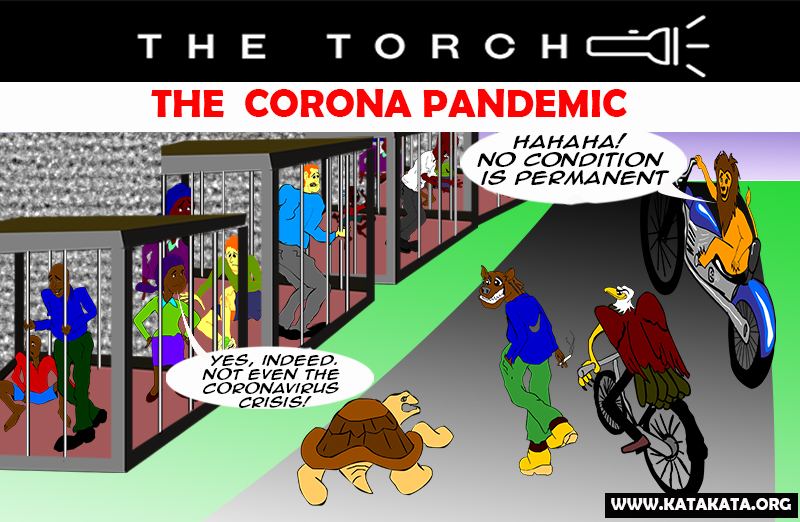

When the Covid-19 stormed the world two years ago and snatched millions of innocent souls, many governments mainly focused on preventing the virus and curbing its spread. They wanted to achieve that by initiating mandatory lockdown, followed by quarantine and isolation for infected ones. But they hardly paid attention to the psychological impacts of the lockdown – especially on the youth and vulnerable ones.

Today, with many governments celebrating their victory over Covid-19 infections and death tolls, which seem to be under control, another pernicious epidemic has aggressively manifested, taking many lives with it. Thanks to the Coronavirus epidemic, mental sicknesses, including depression, which may lead to suicide, have suddenly skyrocketed. Loneliness, fear of infection, grief and suffering over the death of loved ones, and fear of financial uncertainty all have contributed to anxiety and depression. With excessive work pressure on health workers and their daily exposure to thousands of deaths, many faced exhaustion while others committed or contemplated suicide.

According to the World Health Organization, mental health is a condition of well-being in which individuals recognise their abilities, cope with daily stresses, work productively, and contribute to their community. Therefore, mental illness is a state that can affect the above negatively, regardless of one's age, sex, race or ethnicity.

Specific issues may increase your chances of developing mental illness, such as a history of mental disorder among your family members, stressful life situations, such as financial problems, or the death or divorce of a loved one. Other medical conditions, such as diabetes and brain damage resulting from a severe injury, are all risk factors.

Others include traumatic experiences, such as assault, alcohol or recreational drug use, a childhood history of abuse or neglect, and a previous mental illness.

Signs of mental illness

Some possible signs of mental illness include:

- Withdrawing from friends, family, and colleagues.

- You consistently have low energy.

- Too little or much eating.

- Sleeping too little or much.

- Unable to complete daily tasks, such as eating, cooking, and going to work.

- Avoiding what one used to enjoy doing.

- Feeling hopeless frequently.

- Experiencing delusions.

- You use mood-altering substances, such as alcohol and nicotine.

- Hearing voices.

- Having persistent thoughts or memories that re-appear regularly.

- Having an idea of causing physical harm to themselves or others.

- Being often confused.

- Having negative thoughts and emotions.

A report released in March 2022 by the World Health Organisation confirmed a massive 25% global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

SARS-CoV-2.

Recent research has revealed that fear, isolation, trauma and uncertainty caused by COVID-19 have caused alarming damage to mental health, with depression and suicide increasing. When the novel virus struck, people were confined to their homes by the lockdowns imposed by various authorities to curb its spread. Travelling and gatherings were prohibited in many countries, forcing people to stay day and night indoors. These strict but necessary social measures prevented people from social interaction, including sometimes accessing medical care. In many cases, a lack of knowledge and misinformation about the virus fueled fears and discouraged people from seeking help. Mental health services were also severely impacted, and in most cases, the governments frequently deploy personnel and infrastructure to COVID-19 relief efforts.

As a result, Covid-19 raised the rate of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic disorders, particularly in COVID-19 patients or people who had contact with COVID-19 victims or those who had lost their sources of income. Worse still, many students and pupils had to remain home, causing fear of academic disruption. Due to extended school and university closures, young people have been left vulnerable to social alienation and disassociation, which can fuel anxiety, uncertainty, and loneliness and lead to affective and behavioural problems.

According to a study conducted in China, anxiety and depression rates increased by 30% and 17%, respectively, among the Chinese. Another research in Italy found increases in post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression, and anxiety of 37, 17.3, and 20.8 per cent, respectively. The alarming result was not different in Spain, where 18.7 per cent of people had depressive symptoms, 21.6 per cent had anxiety, and 15.8 per cent had Post Traumatic Stress Disorder due to the coronavirus epidemic. The USA reported that approximately 4 in 10 adults in the country had symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder during the pandemic, up from one in ten adults in January 2019. Few studies on the psychological effects of COVID-19 lockdown on the African population are available, but it is evident that the story is not the same on the continent.

Young ones and women.

The WHO Corona pandemic has affected the intellectual fitness of younger people, many of whom may be disproportionally vulnerable to suicidal and self-harming behaviours. Additionally, the study shows that women have been more critically affected than men. Furthermore, the research reveals that those with pre-existing physical health challenges such as health problems, cancers and asthma have more chances of developing signs and symptoms of mental health problems. Equally, people with pre-existing mental issues and young people are more likely to suffer severe mental disorders and therefore are at significant risk when infected with COVID-19.

Family Problems.

Forcing children and adolescents to stay at home may have increased their risk of experiencing family stress or abuse, both of which are risk factors for mental health problems. Women have also reported more stress in their homes, with some studies showing that during the first year of the pandemic, women experienced some form of physical and mental abuse, directly or indirectly. Aggression has become the order of the day, caused by disruption of the typical mainstream social system.

A higher proportion of young adults reported anxiety and depressive disorder symptoms during the pandemic than adults. They also reported a rise in substance abuse and suicidal ideation. These social problems result from pandemic-related consequences, such as university closures and income loss.

Job loss was linked to increased depression, anxiety, distress, low self-esteem, increased substance abuse disorders, and suicide. Adults in households with job loss or lower incomes reported higher rates of mental illness symptoms during the pandemic than those without job or income uncertainties and failures, which put enormous pressure on the family.

Mood Disorder

According to WHO data, one in every eight people has a mental disorder, with anxiety and depression being the most common. Depression and anxiety are the two common forms of mental illness. Depression affects over 264 million people worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020). Every year, over 700,000 people commit suicide due to depression. Suicide is also the common cause of death among people aged 15 to 29, while depression is more common in women than men.

Following the World Health Organization's statistics, 5% of men and 9% of women experience depressive disorders in any given year. Due to fluctuating hormone levels, women are especially vulnerable to depressive disorders during menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth, and perimenopausal.

There are three mood disorders: single episode depressive disorder, recurrent depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder. Single episode disorder refers to the person's first and only episode, whereas recurrent depressive illness refers to the person's history of at least two depressive episodes.

Depression and manic-depressive episodes, on the other hand, alternate with periods of bipolar disorder symptoms such as euphoria or irritability and an increase in energy and activity, as well as other symptoms such as increased talkativeness, racing thoughts, an increase in self-esteem, decreased sleep needs, and reckless impulses.

Recommendation

The apparent increasing effects of the COVID-19 on mental health conditions had already forced many countries to incorporate mental health and psychosocial support in their COVID-19 response plans. That is a good step in the right direction, but we must do much more. The WHO advises that nations take the following actions to reduce the COVID-19 pandemic's effects on mental health:

- Apply a whole-of-society approach to promoting, protecting, and caring for mental health.

- Include social and financial protection for victims of domestic violence or impoverishment.

- Widespread communication about COVID-19 to combat misinformation and promote mental health.

- Ensure public access to mental health and psychosocial support, including expanding self-help options.

- Support community initiatives.

- Help COVID-19 recovery by establishing long-term mental health services.

When we talk about the impact of the coronavirus, we should not only focus on the deaths, loss of income, jobs, and lockdown; we must not forget mental disorders, the latent but deadly aftermath of the pandemic. The early we pay attention to the devastating mental health problems associated with the virus, the better we prevent the often less-mentioned menace of the epidemic.