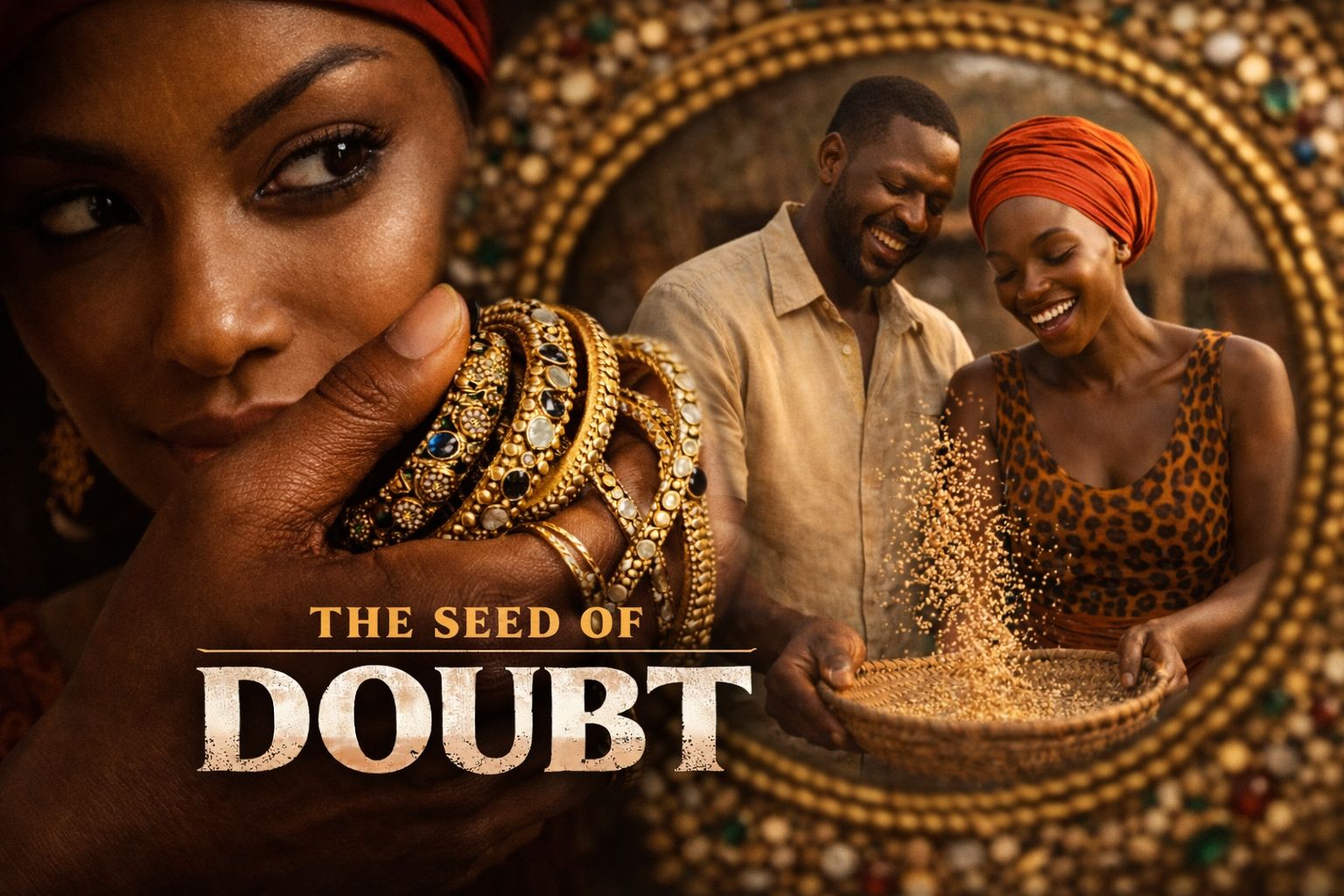

The Weight of Gold and the Lightness of Peace.

In many societies, wealth is not merely a means of comfort; it becomes a language of power. Gold glitters not only on wrists but in the social imagination, signalling status, success, and supposed superiority. Yet beneath this glitter lies a deeper philosophical tension: Can material abundance secure inner worth, or does it merely decorate insecurity?

From a sociological perspective, material display often functions as symbolic capital — a concept closely associated with Pierre Bourdieu. Wealth, when displayed, is not just about ownership; it is about recognition. It seeks validation from the gaze of others. Jewellery, fine fabrics, and rare perfumes become tools in a subtle contest for admiration and dominance. In small communities especially, where social proximity magnifies comparison, the performance of prosperity becomes even more charged. Envy circulates like currency.

But envy is rarely simple. It is not merely the desire to possess what another has; it is often the discomfort of witnessing a form of fulfilment one cannot access. Philosophically, envy reveals an internal fracture — a conflict between one’s outward success and inward dissatisfaction. As Søren Kierkegaard suggested in his reflections on despair, the most dangerous condition is not lacking something external, but failing to be at peace with oneself. When identity is built upon comparison, the self becomes fragile. It depends on others’ reactions for stability.

Attempts to undermine another’s contentment often emerge from this fragility. When material superiority fails to produce emotional triumph, the strategy shifts. Subtle insinuations replace overt boasting. Compliments carry hidden barbs. The aim is no longer admiration but disturbance — to plant doubt where there is harmony. Sociologically, this reflects what Erving Goffman described as the “presentation of self.” Social interactions become stages. Individuals curate appearances not simply to be seen, but to influence the emotional states of others.

Yet the most striking element in such encounters is resistance. There exists a form of power that does not compete. When admiration is returned without insecurity, when beauty is acknowledged without covetousness, and when peace is maintained without defensiveness, the performance of superiority collapses. Wealth depends on reaction. It needs comparison to shine. Without envy, gold loses its sharpest edge.

This dynamic exposes a fundamental philosophical divide between external and internal goods. External goods — wealth, status, adornment — are finite and comparative. One has more because another has less. Internal goods — peace, self-assurance, relational trust — are non-competitive. They are not diminished by another’s abundance. In fact, they are often strengthened by generosity of spirit.

The deeper sociological lesson concerns the limits of symbolic dominance. Material excess can command attention, but it cannot command reverence where there is grounded self-worth. Attempts to destabilise secure bonds reveal the limits of performative power. When individuals anchor their identity in inner contentment rather than public comparison, social hierarchies lose their psychological grip.

In the end, the most immovable force is not wealth but composure. Gold may dazzle a crowd, but serenity disarms it. The question is not what can be displayed to unsettle another, but whether unrest can ever conquer peace. And history — both personal and collective — suggests that it cannot.